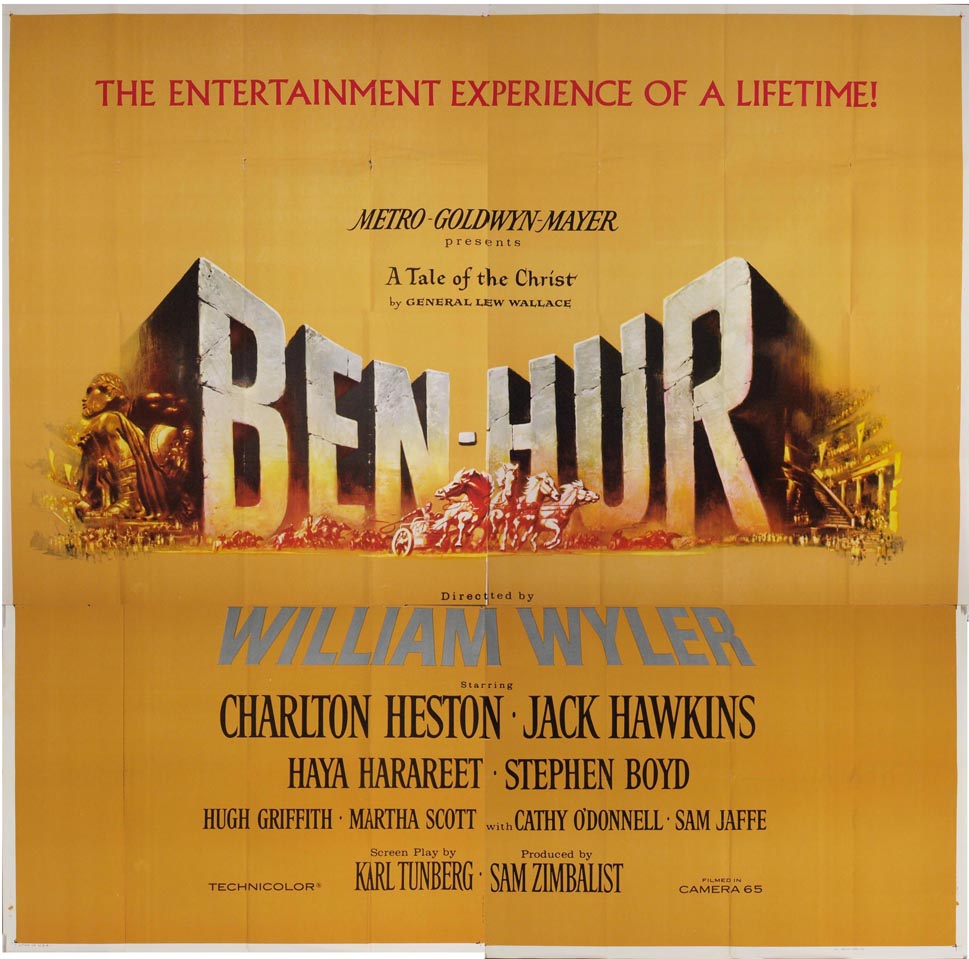

Ben-Hur (1959);

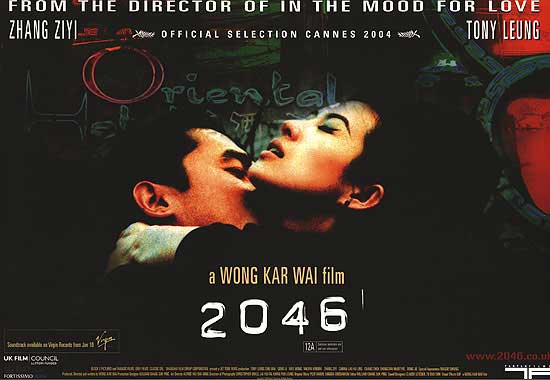

Hail Caesar! (2016)

Directors: William Wyler; Joel and Ethan Coen

I finally bit the bullet and watched

Ben-Hur. For some reason, which I cannot explain, I decided to watch it around this year's Oscars ceremony; clearly one overblown pile of pomp was not enough for me. I would watch 45 mins of the film, then watch a bit of the awards, then go back to

Ben-Hur. I did know also that I was going to go see the Coen brothers' latest film and, considering its many references to such Biblical epics, seeing the ultimate one made sense.

I wasn't expecting to enjoy

Ben-Hur, and unfortunately my expectations were largely met. Out of the whole three and half hours, only two scenes and two performances were really of interest. Stephen Boyd's Messala gets the more complex villain role, moving from friendship (and maybe something more) with Judah to vengeance towards our hero. The other performance is Jack Hawkins' Arrius, whose relationship to Judah goes in the opposite direction to Messala; after trying to break Judah Ben-Hur's spirit, the two save each other's lives, eventually becoming family. The scene on the boat, full of whipping, semi-naked men and death stares, has the best acting the whole film. The battle between Judah and his captors is played wonderfully, and you can almost feel the aches and pains in the slaves' bodies.

The celebrated chariot race is still striking, partly because of its length, which manages to sustain the tension. The energy comes not from the super editing cuts that are a staple of modern action scenes; rather the constant pounding of the horses' hooves, and the cool way the violent crashes are depicted draw the viewer in. And I really wish the film had ended right there and then.

It may sound strange coming from a Christian, but the parts of the movie that bugged me the most were the religious parts, and the reason for this is beautifully depicted in the Coen brothers' film. Early on in

Hail Caesar! Eddie Mannix gathers a group of religious leaders - Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican (?) and Jewish - to discuss the theology of Capitol Pictures' new Biblical epic. While a frank and funny discussion ensues about images and ideas about God according to the Old and New Testaments, in the end they all agree the film's theology is fine, and does not offer any challenging depictions of Christ. And that, for me, is the problem with

Ben-Hur. It is far too tame and obvious in its religiousness (something one could not say about Jesus!), and the thunderbolt and lightning ending is almost laughable; like George Clooney's Baird Whitlock, we are expected to simply 'Squint at the grandeur!'. Give me the awe-inspiring, quiet miracles of Dreyer and Bergman over Hollywood religiosity any day!

After the ponderous seriousness of

Ben-Hur, the fun of

Hail Caesar! was a joy. I knew going in not to expect a strong plot, so instead sat back and let the story wash over me. I laughed throughout, a reaction few modern comedies provoke in me, and loved the glimpses of the meta-films; and someone really needs to cast Channing Tatum in a Gene Kelly-style musical as soon as possible. While I do understand that the lack of a clear plot could annoy some, I didn't really get the hate directed by people towards the film.

This was an interesting double-bill to watch, and if you have the time and the patient to try, I would recommend it.