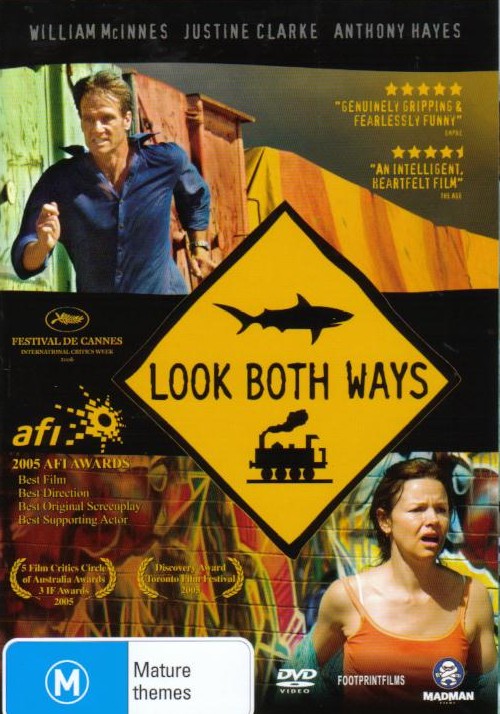

This particular Double Feature looks at two films from Australian director Sarah Watt: Look Both Ways (2005) and My Year Without Sex (2009). Watt had a great flair for animation, using it in both her films. I speak in past tense, for Watt died in 2011 after suffering with cancer for six years.

In Look Both Ways the central story follows Meryl (Justine Clarke) and Nick (William McInnes, Watt's husband) who meet at the scene of a train accident and discover they live near each other. Meryl is obsessed with death, constantly imagining terrible things happening to her, such as the train she is on crashing, drowning at the swimming pool, being held at gun point going outside at night. Nick has recently discovered he has testicular cancer that has spread to his lungs. The train accident that connects them was a young being hit and killed by a train.

In My Year Without Sex Natalie, mother of two, collapses with a ruptured brain tumour and is told not to do any strenuous work for a year, most galling being sex. The film follows Natalie, her husband Ross and their children for the next twelve months as they navigate issues like finances, pets, friends and life in the suburbs along with death, faith and love. Watt's animation is used My Year in a very small way; the film is segmented throughout by inter titles that are words or phrases associated with sex: 'Doggy Style' is used for the segment about the family dog, and the film's climax is called 'Climax.' These are accompanied by images (not pornographic) drawn by Watt.

Clearly, death is a major part of both stories. It hangs over the characters, weighing down their relationships with each other. For Natalie and Ross it removes a significant aspect of their marriage, creating tensions between them; Ross is only slightly tempted by a pretty work colleague, but it is only shown as a passing moment, and is clearly a result of the abstinence enforced at home. Meryl and Nick meet because of a death; Meryl feels that death is a violent force that is following her, while Nick has visions of the cancerous cells infiltrating his body. Nick's situation puts a dampener on any new relationships and thus swiftly tries to end his burgeoning one with Meryl.

The setting for both films is the suburbs, and amongst people living on the cusp of middle-class/ working-class. The characters' focus shifts from the major fears of mortality to the everyday stresses of finance and work, transforming the suburbs to a place of survival similar to the outback. It is not a stultifying place, but just as dangerous as the wild, with death around every corner.Lest this write-up makes these films sound depressing, they are not. There is a gentle vein of comedy running through them, particularly My Year. And, as with many of these films, living life wins out over living in fear of death.

The two films have an added poignancy and honesty knowing what happened to Watts a few years later. It is very sad looking at these two films, knowing that there won't be anymore; Watts' films, though few in number, are idiosyncratically hers. It is a great loss to the Australian film industry.

The two films have an added poignancy and honesty knowing what happened to Watts a few years later. It is very sad looking at these two films, knowing that there won't be anymore; Watts' films, though few in number, are idiosyncratically hers. It is a great loss to the Australian film industry.