I have a theory about the reason why three seems to be a good number for a film series. It really comes down to the classic structure of screen drama: the 3 Act structure. If you are unfamiliar with it, it comes from Aristotle's writings on drama, and underpins most Hollywood films. Act One is the beginning - set-up, inciting incident (spark for action), and often has a significant setback as it climax; Act Two begins with a change of plan as a result of setback, which leads to a 'midpoint' (point of no return), and climaxes with the moment when things look their bleakest (the dark night of the soul, if you will); Act Three begins with a hint of hope that leads to the film's overall climax, is finishes with a resolution (riding off into the sunset). You'll notice the plot points within each act are also grouped in threes.

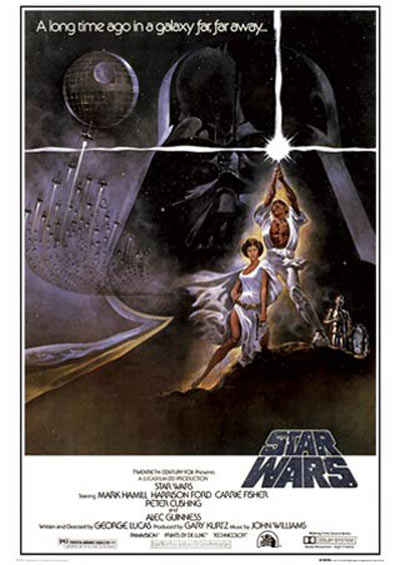

Does this still apply to the various trilogies that we are all familiar with? In the case of Star Wars (Episodes 4, 5, 6), I think it does. Star Wars (1977) is largely set-up of the story's world: the Empire, the Rebel Forces, Luke, Han, Leia, Darth Vader, Obi-Wan, the droids, light sabers, spaceships, etc. There is also the overall spark for the story, which is Luke deciding to follow in his father's footsteps and become a Jedi. This is the Inciting Incident for the trilogy; for the film alone the I.I. is Luke buying the droids. Of course, one could argue that this is also the I.I for the whole series, if Luke didn't find C-3PO and R2-D2 there would be no story. But Luke's choice to become a Jedi affects the whole rest of the story. He could easily have said, 'No thanks, I'll just help you with the droids, but then come back home (and probably die). Instead he says 'There's nothing here for me now.' This propells the story beyond this one film. It also makes the significant setback (Obi-Wan's 'death') all the more significant. How will Luke become a Jedi now!?

The film doesn't end with the significant setback; it has its own resolution, which is triumph for the Rebels as they destroy the Death Star. However, its impact is not that long lasting. At the beginning of Empire Strikes Back it is being rebuilt, a symbol of the resurgent Empire. The change of plan in Empire Strikes Back is Luke decision to go to train with Yoda (this is the change of plan for both internal and external structures of the story). As a result of this change of plan, Luke is made to confront some uncomfortable truths. The trilogy's midpoint shows us Luke fighting and killing Vader (in his mind), only to discover that under the mask its his face. Not only is his a nice bit of Freudian foreshadowing, but it tells us that Luke needs to overcome himself before he becomes a fully fledged Jedi. He will also have to resist the temptation to join the Dark Side. The films famously ends on a dark note (ie the moment when things couldn't be worse). Han is frozen, the Rebels forces are still scattered around the galaxy, and Darth Vader has made Luke very vulnerable.

This movie also follows the exploits of Han, Leia, Chewie and C-3PO via a B-Plot. They wander around trying to evade capture by the Empire, eventually ending up at Cloud City - and walking right into the Empire's clutches. They become the bait for Luke, luring him away from his training. Their plot also develops the relationship of Han and Leia, resolving some of the sexual tension begun in the first film.

The third film begins with a conclusion to Han Solo's B-plot, as Luke, Leia, Chewie and Lando rescue him from Jabba. This successful rescue provides hope for the overall plot; now everyone is back in action, the main antagonists can be dealt with. Return of the Jedi builds towards the trilogy's climax, where the Rebels defeat the Empire, and Luke ultimately chooses to be a Jedi; he even manages to re-convert his father before he dies. The story's resolution sees peace restored to the galaxy. There is also hope for the future, as the Luke, Leia and Han are set to become one big, happy family. Darth Vader/ Anakin also gets a send-off, cremated by Luke on Endor.

Though there are some problems with the story (Ewoks defeat the Empire forces, really?), the overall structure is not one of them. It gives the audience the emotional ups and downs that are traditionally satisfying. It may not be something most fans think about, or even notice, but it is one of the trilogy's strengths.

Do you agree?